Open Source Digital Photography

When you have a look at what software tools photographers - either hobbyists or professionals - use for their work you get the impression that the options concerning software in digital image procession must be extremely limited - much more limited than for example for the camera hardware. To some extent you could nearly say a technique does not exist in the world of digital photography if is not available in Adobe Photoshop. I wrote this introduction into open source tools for digital photography to help anyone stuck in this limited perspective but with an open mind to get started in the world of open source image processing and to get an idea of the chances it offers.

Some time ago i noticed that the CDs or DVDs coming with hardware (including but not limited to cameras) i bought in the last years always stayed untouched in the box. Of course i was always aware of this but it occurred to me how unusual this is apparently when talking and listening to others using similar hardware. It is pretty obvious that not needing to learn and possibly work around the limitation of a new software every time you get a new gadget saves you a lot of time. This means hardware not only just works, it also always works the same way.

As a professional photographer you might be tempted to dismiss open source software as hobbyist toys - and a look at open source use in photography will support this view. Equally amateurs often think they have to use expensive software if they want to do serious work. Such considerations are generally not based on facts though. It has been proven on countless occasions that results generated by open source tools are of equal or superior quality when compared those of much more expensive programs. You can find a collection of arguments for using open source software below but it is important to keep in mind one thing:

Most open source programs are developed by their authors for their own use/enjoyment or for an employer/contractor. As a result the motivation of authors of this software to get you to use their programs is usually much lower than for commercial programs where every additional user means more money. Therefore your motivation is the key to successfully using open source software.

Below i will introduce some examples of open source software that can be very useful for digital photo processing. But this list is no way exhaustive. You can find a lot more - see for example the Raster Graphics Editors and Digital Camera categories on Freshmeat.

If you are not interested in the individual program descriptions but want to know about the arguments for using open source software for photo processing you can skip right to the why should i care?

DCRaw

It is obvious that this list has to start with DCRaw - a tool written by Dave Coffin that reads most raw image file formats produced by currently available digital cameras and converts them into standard PPM or TIFF files. Probably all open source programs reading raw files are based on DCRaw and interestingly also most third party closed source tools that do so make use of Dave Coffin's work somehow. A list of those programs as well as a list of Cameras supported by DCRaw can be found on the DCRaw website.

DCRaw is a simple command line program, well suited for automated conversion of lots of files. For those who have forgotten how to invoke such a program there are of course graphical frontends and most of the software described in the following integrate DCRaw's features or are able to invoke it when needed.

DCRaw extracts the the image data from the raw files and writes it to linear 16 bit files for further processing - you can choose between several algorithms for the Bayer pattern interpolation. In a lot of cases the results that can be obtained using DCRaw converted files when properly used are much better than those generated with the software usually coming with the cameras. It can also apply ICC profiles, set white balance and remove bad pixels caused by broken sensor sites. DCRaw can extract and use those meta information in the raw files considered important for processing the images like the white balance or the EXIF data but does not try to read custom adjustments made in the camera like sharpening that are sometimes read and applied by the software coming with the camera.

DCRaw is a highly portable ANSI C program that can be built and used on almost any computer platform. Using it is also a good insurance that your raw files stay readable in the future.

Krita

Krita is a general purpose imaging program. It underwent a fairly rapid development in the last 2-3 years and is meanwhile mature enough for production use although some aspects, especially the ease of use for common tasks, are improvable. The keyboard shortcuts for the program functions are something to get used to but once you do they are very consistent. Some important features are still missing though - for example there is no 'levels' adjustment tool and some simple manipulations like brightness/contrast or simple thresholding can currently only be achieved with tricks. It integrates full color management and support for different color spaces as well as different color depth images including 16 bit and 32 bit HDR modes.

Krita is a KDE program so it can be used on all platforms supported by KDE. Of all open source general purpose image manipulation programs it is definitely the most solid design - with signs of incompleteness in some areas though.

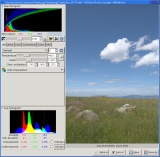

UFRaw

UFRaw is a graphical frontend for DCRaw with some additional features. With it you can adjust the DCRaw options like white balance, ICC profiles and interpolation methods with immediate feedback about the effect on the image. Furthermore you can manually adjust color transfer functions.

UFRaw can save your adjustments to a file and apply them automatically to a lot of files in batch mode. The results can be written in 8 or 16 bit PPM and TIFF format as well as JPEG images. One major limitation is that UFRaw can only load raw files from the camera and not normal TIFF files like for example panoramas assembled from multiple photos.

UFRaw can be used on a large variety of computer systems. Compiled versions are available for a lot of Linux and BSD distributions as well as Mac and Windows systems.

Digikam

Digikam is an image management program. You can use it to browse your image collection as well as apply image editing and conversion tasks. Digikam offers a lot of features (much too many to be all described here) and even bears the risk to become overladen with features meanwhile. So if you are just looking for a simple tool to browse your image collection Digikam might already be too much. If you are looking for something to manage your photo collection including image download from the camera, tagging, notes, slide show presentation etc. Digikam almost certainly offers what you need.

All the information entered about the image (tags, comments etc.) is stored in a SQLite database so it can easily be extracted and used by other programs.

Digikam, like Krita, is a KDE program so it can be used on all platforms supported by KDE.

LPROF

LPROF is an open source solution for generating ICC profiles. It is built upon the LittleCMS open source color management system. Various Linux distributions include a copy of LPROF and a compiled version is also available for Windows. On other platforms you can easily build it from source.

What LPROF does is reading a photo/scan of a reference target (like for example one of those on coloraid.de) and the corresponding reference file and generating a profile containing information on the color reproduction characteristics of this device. Using this profile color management aware software can correctly read the images generated by this device and can accurately convert the colors into a working color space.

LPROF also supports monitor calibration.

Hugin

Hugin is an interactive version of the Panorama Tools suite for stitching panoramas by coordinating several overlapping images and transforming them to a common projection. Hugin allows to adjust all the parameters for this interactively - you can set the control points, calculate the camera/lens parameters and preview the resulting image. It can integrate several programs for automatically finding control points and use different programs (including Enblend) to blend the resulting images.

Hugin can also be useful for other purposes than panorama stitching - it can be used for correcting lens distortion, chromatic aberration or perspective correction or for assembling partial scans.

Enblend

Enblend is probably the most outstanding program in this whole list - both in being a simple elegant design and in producing results of outstanding quality. If you are doing panoramas from multiple shots and you are not already using Enblend this is surely a good point to start with.

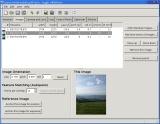

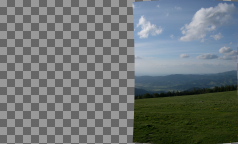

Enblend is a good example for the do one thing, do it well approach. The thing it does (and the only thing it does) is blending several overlapping image into a single one. When doing panoramas you create several input images where all the image area except that part actually covered by this particular image are transparent. Enblend stacks these files and blends all the regions covered by more than a single input image. For this it analyzes the image content and adjusts the blending accordingly.

The images are not only blended very well - Enblend is also quite versatile with the supported input formats. You can use it for 16 bit files as well 32 bit floating point images and it can blend very large panoramas without problems.

|

|

|

| input images | ||

|

|

| images stacked without blending | blended with enblend |

ImageMagick

ImageMagick is something like the swiss army knife of image processing. It can be used for just about any image file format conversion you might need. Furthermore it can do various manipulation tasks - like simple scaling (with selectable scaling algorithms), adding copyright notes, applying filters, cropping, rotating and much more. All these can be applied from scripts using the convert, mogrify and composite tools or using the various Imagemagick APIs for a programming language of your choice. Many web gallery generators for example make use of ImageMagick to produce thumbnails and scaled down versions of the images.

CImg

CImg is in fact not a program but a programming library that will not be of much use for non-programming photographers. None the less i include it in this list since being able to code your own image processing functions is deemed necessary or useful by quite some photographers. CImg simplifies this for the C++ programmer since it takes care of all the standard underlying functionality like image file reading and writing. CImg also includes state-of-art image processing functions like the famous GREYCstoration image restoration and noise reduction algorithm.

GNU Make and Bash

You might wonder what those have to do with processing photographs. Make is a tool widely used for compiling programs from source, it manages dependencies between different files and takes care of re-processing those (and only those) files that depend on others that have been modified. For photo processing this can be very useful since starting from the raw files from the camera there are usually multiple processing steps with several programs involved. Makefiles are especially convenient for more complex tasks like panorama stitching - Hugin for example demonstrates how it can be used for that. Bash is the most widely used shell scripting language on Unix systems and can be very useful for scripting tasks.

For both programs there of course exist countless open source alternatives - you can choose whatever is most convenient for you or what you are already acquainted using.

How about the cameras?

This is a dark corner of course. Digital cameras are completely closed systems. Every camera owner essentially depends on the manufacturer for software updates. Furthermore the secrecy also extended to the file formats and hardware interfaces - file formats are even artificially obscured to make it more difficult to read them and for remote control and external power supply cameras commonly use nonstandard plugs without specifications being available. But there might be a chance for things to change at some point. For mobile phones for example the first open source platforms are being introduced right now. The same reasons that triggered this development for mobile phones (the increasing costs for developing and maintaining the software for the phone companies and the obvious advantages of a scalable and unified platform) will become increasingly important for cameras as well. But don't count on this happening very soon.

Why should i care?

Good question. There is a general technical and a more photography specific answer:

From the technical standpoint: there are several advantages of using open source tools for your work:

- Open source as an instrument of software quality control: How many times have you been annoyed with a bug or an unhandy design of one of the programs you are using? Of course open source programs also have those. But due to the open nature of the programs these are self-regulating: If there is an annoying problem in a program and even if the author is not willing or able to change it there is usually a programming-savvy user of the program offering a fix very soon. This is not just wishful thinking, countless examples show this is actually working. And if you have a very individual concern about some aspect of a program you can always put hand on it yourself or hire someone to do it for you.

- Workflow stability: This probably requires a bit more explanation. Learning to use, especially truly mastering a computer program usually takes a lot of time. Managing several programs (and of course the camera) to work together for best results even more. Once you replace or update one of the tools the whole work usually starts again. With open source tools you have several advantages concerning this: First open source developers - in contrast to companies who need to sell their new version - usually have no interest in changing things to work differently just for the sake of change. So a new version of an open source program is less likely to feature pointless cosmetic changes. Apart from that it is much easier to continue using an old version if you need to. If you have ever continued using a commercial program way beyond its 'end of life' intended by the company selling it you are probably acquainted with the usual update dilemma - once you update your hardware or operating system you have to realize it does not work any more and you have to either stick to the old system on the whole or move on completely. And if the company discontinued the product line or went bankrupt things look even worse. Programs that can be built from source are much more flexible to be used on new hardware and after an operating system upgrade.

- Platform independence: I just already touched this point - Most of the above programs as well as most other open source software can be used on nearly every kind of computer system. This might not be of enormous importance now but it very likely that this will also be valid in five or ten years for the then current hardware and operating systems.

- Long term accessibility of files: This is understood to be an important issue by many photographers. The lack of a widely accepted open standard for raw images is the most obvious aspect of this problem. One possible approach to address this is to convert all raw images to a standard format but when using proprietary programs this is a two-sided sword: You cannot be sure the conversion retains all important information from the original files. DCRaw and all programs based on it offer you an elegant way to ensure the original raw files will stay readable for the foreseeable future. At the same time you know the processing applied to the images stays reproducible as well.

- Leading edge technology: Open source programs often implement techniques very soon after they have been invented. In fact a lot of research results on image processing are demonstrated in form of open source tools by the researchers. If you have a look at new functions in commercial programs advertised as new innovative techniques you can find that those often have been available in open source programs previously.

- Less costs and license troubles: This is mentioned last since it is nearly never the only reason for people using open source - it none the less can be an important advantage. Furthermore open source keeps you from the need to spend time with license considerations - like if you can use some reduced price software for commercial purposes, if you can install and use a program on your workstation and laptop at the same time etc. No hardware locking or dongles, no registration requirements.

Specifically as a photo artist: If you are not convinced by the above arguments you probably shouldn't. The vast majority of photographers do not use open source tools for their work. Many of them are making good photos none the less and crappy images won't look good just because of the software. Photography is a fairly technical field of art though. Most photographers are pretty delicate about their hardware equipment and some can engage in heated discussion on lens quality, camera brands and models etc. And while a lot of you are competent in optics and other camera technology and also frequently use photo equipment in ways it was not designed for such innovative activity often ends when it comes to the software side of the whole process. Few have the guts of learning how conversion of a raw file into a jpeg image actually works or how a sharpening filter actually modifies the pixels of an image. It is fine not to care about this since - like the camera, lenses and other hardware issues - this is completely secondary for making good images. But if you are interested in such aspects, want to choose your image processing techniques with care and consideration or want to use innovative and experimental post processing on your pictures, open source software offers you a lot more options than commercial programs.